The Legacy of Mondrian’s Aesthetic

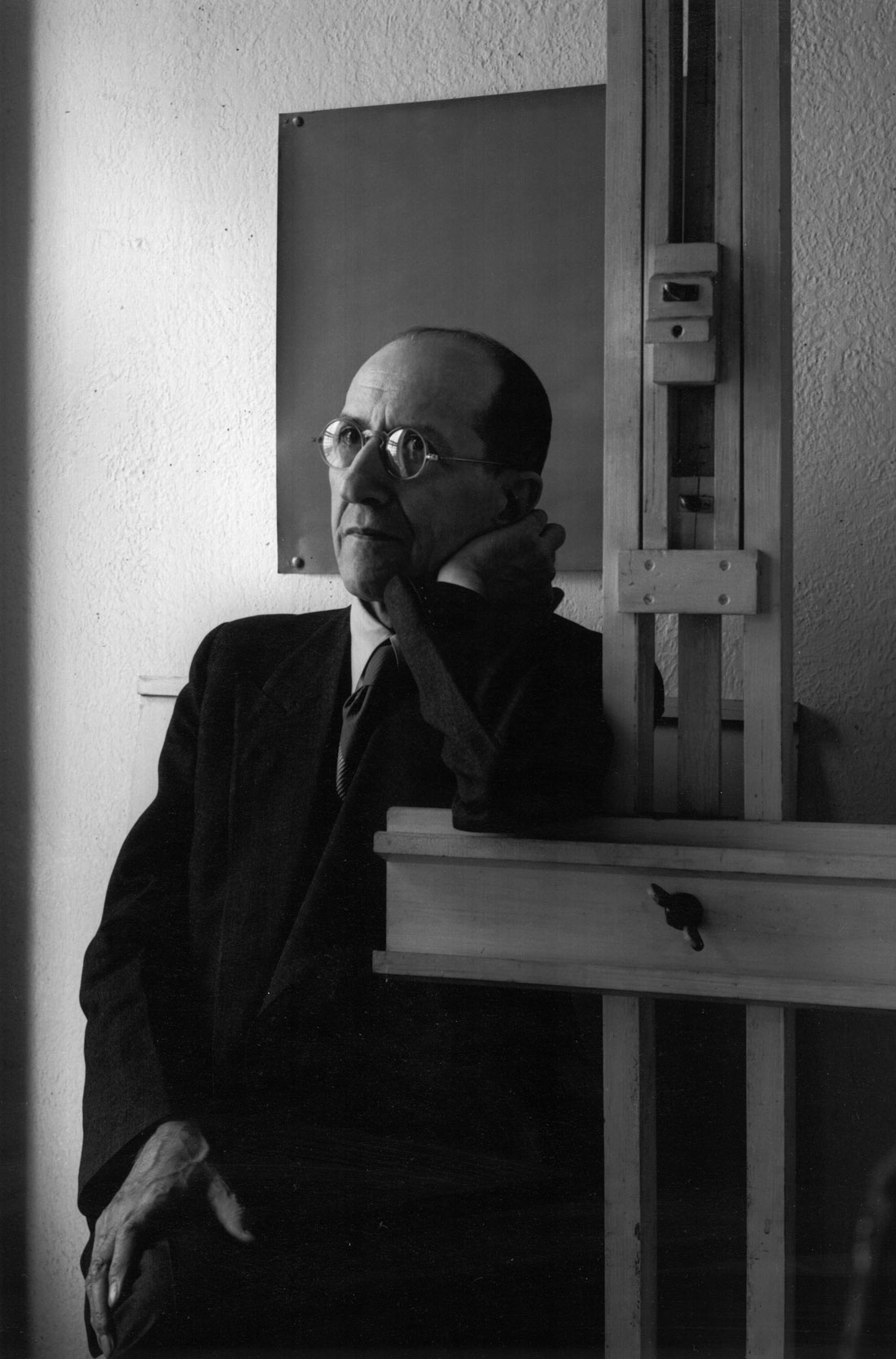

Within the strictest confines of precision, and by limiting himself to only the purest essence and most fundamental building blocks of art, Piet Mondrian utterly rewrote the rulebook for the construction of the masterpiece. In doing so, his pioneering abstract paintings and compositions formed an aesthetic which would go on to shape the 20th century, and influence every corner of the art world and creative industries, even reformulating the way we approach visual culture in its entirety.

From the Dutch pastoral paintings of his youth, through highly individual and iconoclastic interpretations of Post-Impressionism and Cubism, the evolution of Mondrian’s artistic style developed alongside his journey to Paris, and his exploration for a sense of self. By 1914, he was producing the paintings which cemented his stark and particular brand of minimalism, and carving a distinctive visual path he would follow for the remainder of his lengthy career.

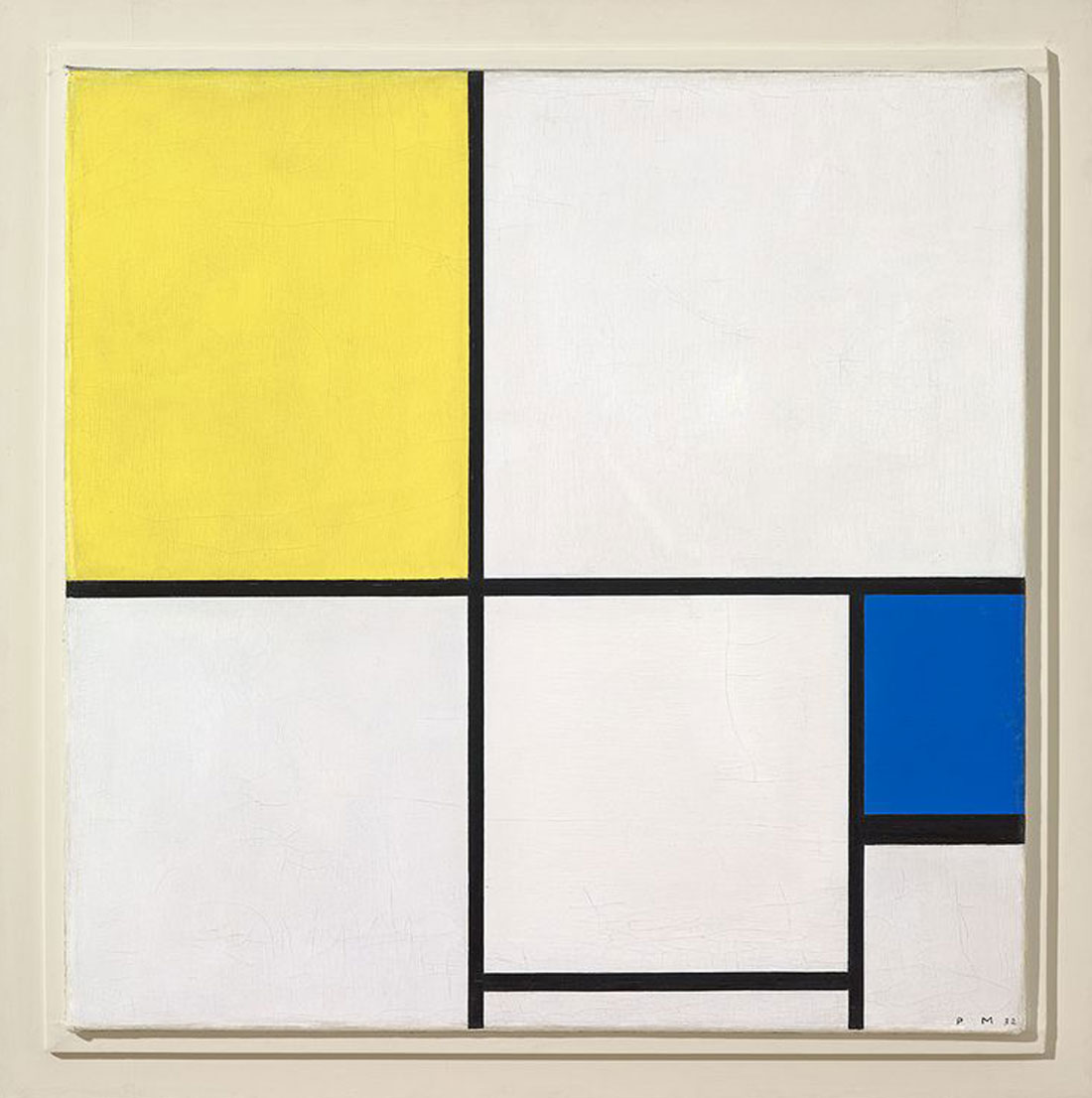

When asked about the creation of his Compositions, Mondrian claimed his approach was informed by an attempt to focus solely on the emotion, which the purity of line and colour create.

The impact of Mondrian’s Compositions was immediate, and laid powerfully influential foundations that galvanised artists and art movements across Europe. Indeed, those Compositions almost instantly established one of the most recognisable artistic vernaculars in the canon, which, while often imitated, were possibly never bettered. While other Minimalists reduced, Mondrian purified, distilled, and refined.

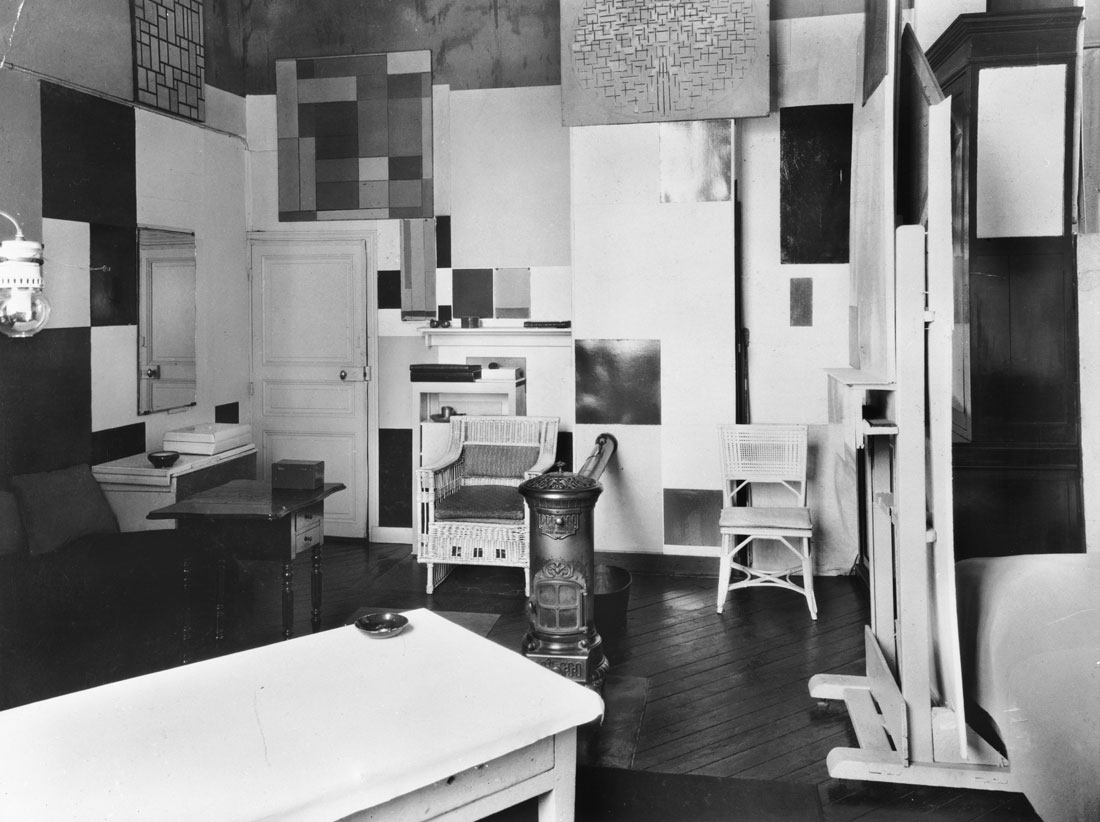

Mondrian approached the creation of the Compositions with all the meticulousness one might expect from a pioneering artist, and his studio at 26 Rue du Depart in Paris played a central role in his practices and methods. Flooded with natural light, thanks to two vast windows which illuminated an irregular five-sided room, the studio was said to be blindingly white, with just a few planes of red or blue interrupting the stark monochrome. His studio wasn’t just a place in which to paint, it was an extension of the paintings themselves, and the ideal space in which to lose oneself in the harmonious construction of colour and line.

Despite first appearances, Mondrian’s lines and colours were actually hand painted, with brushstrokes carefully and purposefully built up over time to create the appearance of a solid plane. The approach was cautious and meditative, with the straight black lines applied first to the canvas, followed by the application of coloured cut-outs, arranged until harmony was achieved, which were then removed and replaced with paint of the corresponding primary tones. The completion of each composition often took weeks, even months, to achieve.

Mondrian’s approach to painting was an idiosyncratic one, demonstrating his commitment to rewriting the rulebook of what contemporary art could and should be. Unlike perhaps every other fine artist before him, Mondrian painted horizontally, with his canvas laid flat upon a desk in the centre of his monastic studio, allowing him a new perspective on painting, both metaphorically and literally. This technique would go on to be instrumental to 20th century art, not least when Mondrian began inviting Post-Expressionist artists to his second studio in New York. Before long, Pollock, Rothko, and other monumental US-based painters would emulate Mondrian’s methods, further innovating and broadening the horizons of what painting could achieve.

Finding deeper meanings in Mondrian’s key works is something both universally accessible, due to shared cultural understanding of colour, yet at once obtuse and challenging. Mondrian himself is a prime example of this dichotomy, as he was publicly bemused by philosophical explorations of his work, while also openly inspired by his own spiritual navigations in forming order from what he saw as a chaotic universe. What cannot be denied, however, is the enduring influence Mondrian’s work had on creatives of all types, with artists, designers, architects and more using his paintings as inspiration.

It wasn’t until the latter part of his career that Mondrian more prominently applied meaning to his paintings, and more explicitly explored how his style could be interwoven with the merest semblance of a narrative. In New York, Mondrian was greatly influenced by the jazz and boogie woogie sounds he’d loved throughout his life. The canvases he produced there evoked urban dynamism and musical rhythm, and resembled grid-like cities lit by neon, bringing a synaesthesiac essence to his signature style which combined music and colour to spectacular effect.

The paintings produced by Piet Mondrian both in his iconic Paris studio and in New York weren’t just radical departures from figurative art, or a new approach to abstraction. They were the starting point of contemporary visual culture as we know it today, with perhaps all non-figurative art of the 20th century and beyond tracing itself back to his black lines and primary blocks of pure and unmixed colour. Mondrian’s minimalist aesthetic sent ripples of influence far and wide, becoming a key design aesthetic of an entire century, appearing as aspects of architecture, inspiring mid-century graphics, and even showing up on catwalks and in haute-couture. Indeed, through Mondrian’s simplicity and his essence of artistic harmony, the world as we know it was coloured anew.