THE SHAPE OF LIGHT

Ever since the blazing creativity and relentless modernism that burst from the Bauhaus, artists, photographers, and architects have sought to utilise shape and light, the building blocks of art and vision, in increasingly ground-breaking and genre-defining ways. This interplay between form and light is perhaps never more evident, nor ever more impactful and impressive, than through the medium of architecture, in which light and shape become at times both one and the same.

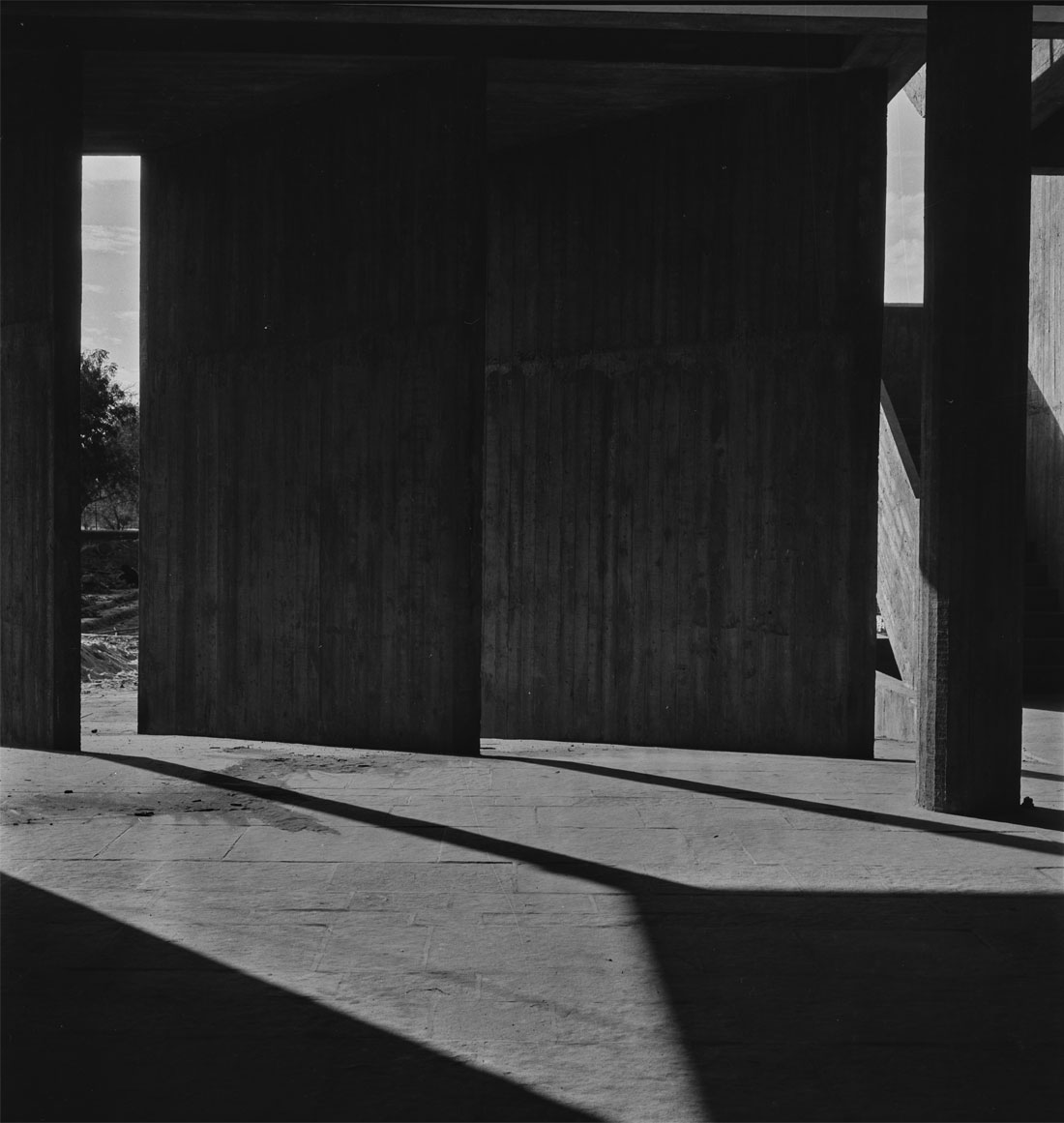

While modernism was far from the only artistic movement to prioritise light, not least in architecture, it did gift the world with the striking combination of bold new buildings, and even bolder approaches to documenting them photographically. The modern world, via the prism of the mid-20th century, was utopian, angular, sleek, and iconoclastic. Captured on camera, and with an architectural use of light as both subject and inspiration, the static and sculptural becomes kinetic, and light and shade dance across metal and stone, pulling the eye around hidden corners, and along swooping lines.

Few artists with architecture as their preferred subject have enjoyed the lasting impact achieved by Lucien Hervé. Inspired by the geometric and expressionist innovations of Moholy-Nagy and Piet Mondrian, Hervé’s approach to image making displayed a fearless fixation on light and form and defined much of his lifelong career, one which will forever be associated with Le Corbusier, the Swiss architect and modernist pioneer. Le Corbusier saw form and light as essential components of the architect’s vision, and his use of light was as playful as it was dramatic. It could inspire a sense of the divine and the essence of the poetic in his sacred buildings, just as easily as it could bring indoors the beauty of the sky, the far-reaching horizons, and an essence of optimism and infinity in his municipal structures.

In the eyes of modernist architects, light presented endless opportunities for bringing fluidity and kineticism to solid structures. Curved corridors featured shadows which would undulate with the changes of the day. Light and shade would compress and expand in waves against blank and sculptural walls. No wonder that Hervé saw in Le Corbusier’s buildings the ideal subject for his modernist photographic experiments. Indeed, after visiting his Unite d’Habitation in 1949, Hervé mailed the architect 700 photographs taken of the building in his own avant-garde style, leading to a truly fruitful meeting of minds.

As Le Corbusier’s monumental leaps forward in Swiss architecture were reshaped ideas of what buildings could be, Hervé’s photography communicated the experience of walking through them. The formula was set. The architect moulded light like clay, teasing it through multi-angled windows, against straight lines, and along smooth curves, and the photographer framed, shot, and froze it for posterity.

The professional relationship between the two pioneers flourished, and their appreciation for each other’s artistry was mutual and dynamic. Indeed, Le Corbusier claimed that Hervé’s artwork represented the end of his 40 years search for a photographer whose way of seeing matched his own. Hervé’s echoed the architect’s words in return, proclaiming that “architecture is the wise, precise, and magnificent balance of forms assembled in the light”.

Hervé’s view of architecture with light at its very core is fundamental to understanding the impact of Le Corbusier’s buildings, and his photographs offer a view of his creations which reflect this impeccably. On film, the architect’s meticulously planned and constructed lines sweep and curve, walls billow, and shadows are cast dramatically in filmic fashion. The eye is drawn into the darkness, and the light which slices through it comes, over and over again as a jolting surprise. Small details, surface textures, and minutae invite exploration, and the endless, unknowable, blankness of the sky is never far away.

Juxtaposition and contrast have been key architectural tools since time immemorial. Le Corbusier’s use of light allowed him to take his preferred materials, namely poured concrete, and instil them with nuanced juxtapositions, rhythms, and a textural playfulness. Wall-to-ceiling windows, decorative wall cut-outs, skylights, and slender supporting columns didn’t just allow light to pour in, rather, they allowed light and shade to define the interior space, and to heighten the purpose and utility of the building itself.

While this is perhaps most obviously evident in Hervé’s photographs of Le Corbusier’s sacred architecture, wherein the architect’s approach to brilliant light and meditative darkness is at its most prominent and symbolic, Hervé ensures that this essential aspect of Le Corbusier’s vision is intact in every single image; elevating it, quite rightly, to the forefront of the viewer’s mind. From municipal buildings in India to offices in Paris, and from homes to holy spaces of quietude, we see that all-important interplay of sunlight and space not as a stylised flourish, but as the foundation on which these buildings are constructed.

Le Corbusier claimed that Hervé was a photographer with the soul of an architect, but to look through Hervé’s images of these remarkable examples of Swiss craftsmanship is not merely to admire the form of buildings. It is to live the experience of moving through real space, and to encounter illumination in man-made forms. They are a testament to an oft-overlooked power; the power of light, in the hands of an artist, to transform monumental buildings into expressionistic spaces, and into something weightless, abstracted, and as endlessly compelling as the sky against which they stand.

Inspired by Le Corbusier’s research on light and shape, the scientists at La Prairie sought to explore how light reveals shape and how shape reveals light – particularly in the three-dimensional landscape of the eye area. Indeed, shape and its influence on how light interacts with the planes of the face – and in particular the graceful curve of the brow, the contour of the lid, the mystery of the lashline – is the defining element of the eye’s architecture.

The result of their findings is White Caviar Eye Extraordinaire, a rich, delicate creation that illuminates the unique architecture of the eye – an area of curves and angles, creating contrasts and shadows.