EYES IN FOCUS

From Ancient Egyptian kohl to Greco-Roman sculpture and Old Master portraits, woman’s unwavering gaze has remained timeless. No matter the medium or the context, it penetrates. Two eyes or one, unmasked or veiled in secrecy, the sweeping understanding of its power and luminescence remains indisputable across cultures in art.

Although Egyptians and Romans proved the power of the gaze, it was later paintings, and photography, that were particularly captivating. For example, Study for an Odalisque by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), features a fair-skinned figure, turned towards the viewer. Set against a dark background, her form glows in a near-unearthly pallor in stark contrast to the shadow.

Ingres was a Neoclassicist, an artistic period defined by a return to detail and discovery. As such, the Odalisque was a recurrent motif of the period. Supple, fair-skinned forms were exposed in the nude. But despite the full exposure, the example is still mysterious—her gaze remains uncertain, cast off into the distance.

Ingres’ work bears strong reference to a photograph of Countess de Castiglione, dated to the 1860s. This was just around the time of Ingres’ death, since Pierre-Louis Pierson was active during a similar period, opening his studio in the 1840s.

The countess’ composition is similar, as turns her face to the right with shoulders exposed. She too bares just a single eye, but this time the shadow comes not from the foreground. Instead, the countess holds a vignette frame to her eye, acting as a carefully concealing mask. The shape of the oval around her eye is quite similar to the rounded shape of Ingres’ beauty’s backdrop, but the woman gains control, all-seeing while the viewer cannot quite devour her form with their own eyes.

The biggest difference was the daguerreotype, named after its inventor Louis Daguerre. Earliest common form of photography, the daguerreotype technique changed the way the world was rendered—it was a far cry from the old world-style of meticulous painting and realism, instead Pierre-Louis Pierson was looking closely at the world around him with characterisation, allowing the camera to capture the eyes. With photography, one had space in the gaze to see a soul.

Going back beyond the Neoclassicists to the masters themselves, the most captivating gazes have always been created by Leonardo da Vinci. His women gaze with both self-assurance and uncertainty, determined direction but side-cast hesitation. La belle ferronnière proves a striking example: even the woman herself is unknown, with only her dark eyes left to time. She is resplendent, in a glorious red robe, but her flawless complexion and dark gaze endure. Her world, old and dark, was brought to life with Leonardo da Vinci’s masterful depiction.

And yet, centuries later, it was Paul Klee who deconstructed the gaze most powerfully, with bare shoulders, with his Open-Eyed Group painting. The gaze is alarmingly, jarringly revealing—a far cry from the sidelong glances of comely maidens. Skin and eyes dance across the canvas with little regard for composition or colour scheme.

The contemporary art of Paul Klee’s historical moment stripped away the shadow and depth of the Old Masters and photographers, desperately trying to capture the so-called real world. Instead, the figures practically float and jut, striking black and white eyes breaking with tradition. The result is refreshingly stripped away. Gone are the women concealed. They are free to stare and embrace their own majestic purity and sensuality, powerfully rendered with line and shape alone.

From antiquity to the 20th century, a gaze disarms and charms, ignites and delights. These paintings are most powerfully preserved in time, deeply etched in the memories of those who catch the eyes of the subject. Though we will never fully capture the wonder of these enigmatic stares and the beauties they belonged to, we can admire them in spurts of magic. In that way, they last forever.

When we focus on something, we gaze at it. The very word “gaze” is one that evokes intensity, passion, and a propensity to dream. It is frequently used in English idioms - “to gaze longingly”, “to gaze into the soul of another”, “to meet one’s gaze” – but what does this word, so weighted in poetic connotations, actually mean?

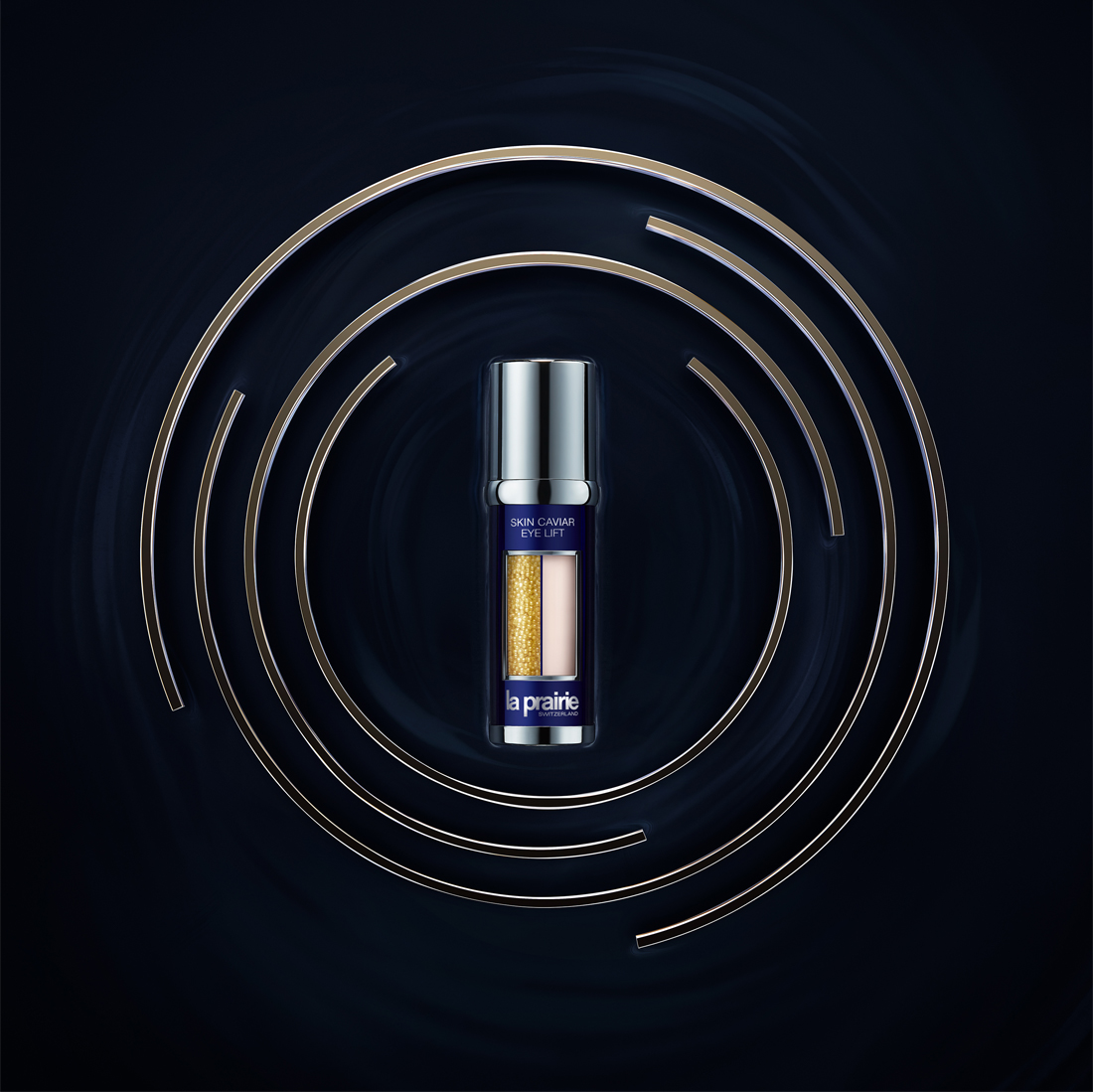

It is this very question, and this emotional, powerful, and defining quality of the gaze that La Prairie explores with its latest creation. At La Prairie, the boundaries of innovation are constantly being pushed, the potency of caviar science is always being enhanced, and new realms of its potential are perpetually being explored. With an infusion of Caviar Premier, the latest caviar incarnation developed by La Prairie scientists, the eye becomes the focus of La Prairie’s Swiss scientific endeavours. Caviar’s full lifting potential is harnessed for the first time to revive, raise and redefine the gaze.

La Prairie introduces Skin Caviar Eye Lift the first eye-opening serum for the whole eye area, including the brows – the gentle yet effective answer to eye lifting and firming concerns. The gaze is raised, revived, redefined, and reawakened with a new appearance, with a new perspective.