THE GIFT OF BEAUTY WONDERS

YOUR HOLIDAY INDULGENCE AWAITS

A timeless exclusive La Prairie pouch designed to accompany you through the holiday season and beyond, with any purchase of £250+.

Additionally, treat yourself to a Skin Caviar Liquid Lift miniature (5ml) with purchases of £500+ and a Skin Caviar Luxe Cream miniature (5ml) with purchases of £1000+.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE

PLATINUM RARE FESTIVE NIGHT INDULGENCE DUO

A celebration of rejuvenation after dark. Skin awakens visibly revitalised, luminous, and youthful.

Platinum Rare Night Elixir

Platinum Rare Haute-Rejuvenation Cream

At a special value online only.

THE ULTIMATE WINTER RITUAL

Embrace the season of holidays with La Prairie’s curated step-by-step product selection.

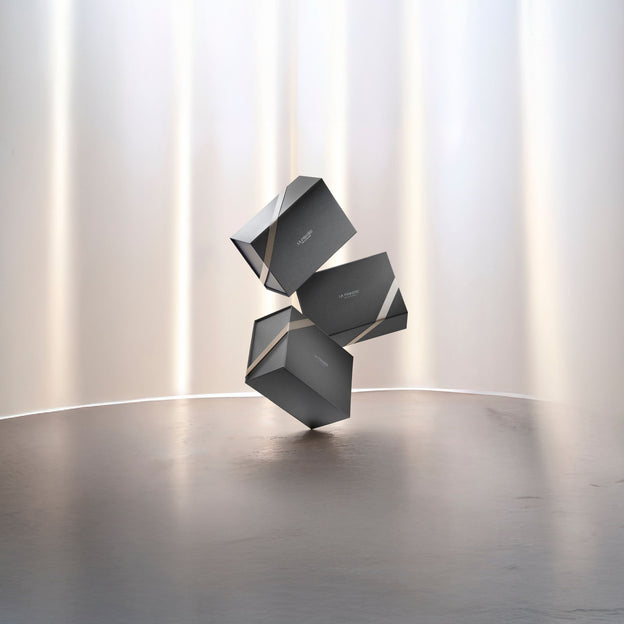

CELEBRATE THE ART OF GIFTING WITH EXCLUSIVE FESTIVE SETS AND DUOS

Whether as a cherished gift for someone special or a moment of indulgence for yourself, these limited-edition sets and duos offer the perfect way to experience La Prairie’s most iconic creations.

LIMITED TIME OFFER

With any purchase of a Night & Day Bundle or Ritual, indulge in a complimentary La Prairie Silk Sleep Mask. For orders over £450+,

delight in an additional Skin Caviar Hydro Emulsion miniature, and for orders over £900+, elevate your ritual with a Skin Caviar Liquid Lift miniature.

A NEW ERA OF REJUVENATION

La Prairie’s intensive treatments designed to deliver an additional boost of rejuvenation.

Platinum Rare Protocol, a month-long intensive treatment. Firming. Volume-Enhancing. Rejuvenating.

Platinum Rare Mask, a two-step treatment to recreate the gesture of today's most sought-after aesthetic procedures.

THE ULTIMATE WINTER RITUAL

Embrace the season of holidays with La Prairie’s curated step-by-step product selection.

OUR HERITAGE

Immerse in the essence of La Prairie

A Swiss luxury house crafting the ultimate skincare to empower discerning individuals to live to their full potential.